Features

Think-tanks think sustainability: #1

In the first of three features interviewing representatives from the UK’s leading think-tanks, Alex Blackburne speaks to Philip Booth, from the Institute of Economic Affairs, about sustainability.

One of Britain’s most influential free market think tanks, the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), has been a prominent player in British politics for over 50 years.

In the first of three features interviewing representatives from the UK’s leading think-tanks, Alex Blackburne speaks to Philip Booth, from the Institute of Economic Affairs, about sustainability.

One of Britain’s most influential free market think tanks, the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), has been a prominent player in British politics for over 50 years.

Indeed, Milton Friedman, a leading economist of the 1970s, said, “Without the IEA, I doubt very much whether there would have been a Thatcherite revolution”.

Formed in 1955 by the late Sir Antony Fisher, one of the most important men in the history of libertarian think-tanks, the IEA scrutinises, and is often sceptical about, many Government initiatives, and sustainability is no different.

Two recent publications on fair trade and climate change – Sushil Mohan’s, Fair Trade Without the Froth and Robert L. Bradley Jr’s Climate Alarmism Reconsidered – show their perspective.

Philip Booth, the IEA’s Editorial and Programme Directors, says of the latter.

“The author of [Climate Alarmism Reconsidered] wished to make clear that there was a series of steps one had to go through before accepting that government intervention would improve things and that some of those steps related to acceptance of the science”.

The report suggests that in some ways climate change is benign, but the main thrust of the analysis, again, is directed towards Government, and its intervention into sustainable development.

The role of the IEA, according to Booth, “is to promote wider understanding – through research and education – of the role that markets play in solving economic and social problems.”

“Bearing this in mind”, he says, “much of the IEA’s work on environmental problems has been to explain how market-based systems and, in particular, property rights solutions to environmental problems can be developed”.

Booth refers back to the IEA’s wider purpose, which is, quite simply, to be sceptical of governments’ intervention in markets.

“Part of the IEA’s work looks at the public choice and knowledge problems of organising Government action. Even if there is a problem here, will the Government make things better? Maybe it will make things worse.

“Perhaps the [Government’s] process will get captured by interest groups or perhaps the interventions will undermine the free economy and reduce adaptability.”

Booth re-emphasises the concern that will remain as long as there is, “the potential for science to be captured by interest groups”, adding that “Government intervention in this field does not have a happy history“.

The only role of government is to provide strong rule of law and support property rights

“[IEA] authors tend to strongly hold the view that both theory and evidence suggest that sustainability is best enhanced by strong rule of law”, Booth states, “[as well as] the development and evolution of property rights in environmental amenities, and the ability to trade those rights.”

As for companies, Booth outlines his thoughts over their role in sustainability.

“I feel [a company’s] main role is to look at their actions and ask themselves whether they are doing things that implicitly infringe the property rights of others, where those property rights are not properly delineated, defined and enforced, either by the state or by some private mechanism.”

He concluded by issuing a warning to those who seek greater governmental, or intergovernmental, action to interfere in markets.

“If the market cannot deliver sustainability we should not look to all-encompassing government regulation to do so.

“The market has been a far more sustainable approach to ensuring prosperity than any other.”

The IEA’s approach to sustainability will undoubtedly challenge the views of many of our readers who would like to see strong government and inter-government intervention. That said they might be on to one important point that we can all agree on.

The underlying message beneath all of this is, if you’re going to act and work sustainably, do it for yourself, as opposed to relying on a government policy that forces you to change your ways.

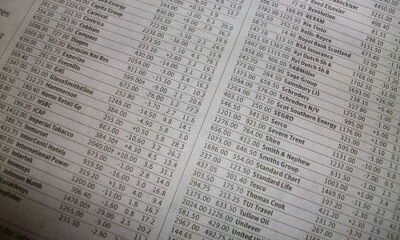

If you would like to find out more about investing in sustainable companies, ask your financial adviser, if you have one, or complete our form and we’ll connect you with a specialist ethical adviser.

Features11 months ago

Features11 months agoEco-Friendly Cryptocurrencies: Sustainable Investment Choices

Energy11 months ago

Energy11 months agoThe Growing Role of Solar Panels in Ireland’s Energy Future

Energy10 months ago

Energy10 months agoGrowth of Solar Power in Dublin: A Sustainable Revolution

Energy10 months ago

Energy10 months agoRenewable Energy Adoption Can Combat Climate Change