Economy

Domestic solar panels as an investment

Ken Richards outlines the investment case for domestic solar photovoltaic panels.

When the current coalition government came to power, the prime minister boasted that his was going to be the greenest government ever, though some of its subsequent actions might cause people to think that this promise is a hollow one. For example, the government has reduced incentives for the installation of domestic solar photovoltaic panels by cutting the feed-in tariff (FiT) rate, reducing the time period over which payments are made, and reducing the amount payable where the energy efficiency of the property is below a certain standard.

This article will show that:

– The monetary benefits of solar panel installation were partly appropriated by the installing companies in the form of higher profits

– The payback method used in illustrations to assess the benefit is seriously flawed, but that a more scientific method shows that the benefits of solar panels are still significant in comparison with other forms of investment

For homeowners who have installations up to 4 kilowatt/hour (kWh) in size, there are three benefits:

– Payment for every kWh of energy produced –the generation tariff (GT)

– A small payment called the export tariff (ET) for surplus energy exported to the National Grid, which is not metered at present but which is assumed to be half of the amount generated

– Not having to pay for the electricity which it produces itself and, for people who are at home during the working day, this feature is even more beneficial as they are able to use power which would ordinarily be exported to the grid

A fourth benefit was that in the case of old-style analogue electricity input meters, the meter ran backwards when energy was being produced, though many power companies subsequently replaced these with digital ones.

For systems installed before March 3 2012, the generation tariff was 43.3p per kilowatt/hour (kWh) and the export tariff was 3.1p, both being increased every year in April by the retail price index (RPI) and payable tax-free for 25 years. Effectively, the total payment amounted to 44.85p per kWh (i.e. 43p + 0.5 x 3.1p). Given that the estimated generation is about 3,200kWh per annum, this amounted to a tax-free amount of about £1,435 per annum, payable quarterly. It was estimated that the amount of electricity saved amounted to 12p per kWh or about £190 per annum, which is also effectively index-linked since the price of power is expected to increase by at least the rate of inflation over time.

As an example of the incidence of the benefit being shared by the producer and the consumer, a quote for a 3.87kWh system was received by the author in mid-October 2011, costing about £15,000, which at the time would give a total annual income of £1,600 and a payback period of 9.4 years (15,000/1,600). At the end of October, the government announced that for installations after December 12 2011, the GT would be 21p, following which another quote was received from the same company for a slightly larger system for about £10,000 giving an annual income of £933 with a payback period of 10.7 years.

Although both economies of scale and technological change have reduced the cost of panels, it beggars belief that these factors alone would have accounted for the £5,000 fall in cost of the installation, particularly given that the cost of the panels themselves account for less than 50% of the total installation.

A successful appeal was made by Friends of the Earth in the Court of Appeal against the reduction in the FiT from December 12, which meant that systems installed up to March 3 2012 also became eligible for the rate of 43p.

For systems currently being installed, a GT rate of 14.7p, frozen until January 2014, applies for houses with an energy performance certificate of band D or better, together with an EP of 4.64p per kWh. The store Ikea is now offering a 3.36kW system for £5,700, claiming that a semi-detached house in Southampton with a south-facing roof would generate savings of about £770 a year, although the Energy Saving Trust suggests that this is optimistic and that a more realistic figure is an annual saving of £600 which gives a payback period of nine-and-a-half years. After 20 years, the householder continues to benefit from producing electricity for a further five years as the expected life of the panels is about 25 years.

The payback method used by companies to illustrate the benefits of solar power is unsatisfactory in several respects namely that it:

– Ignores the foregone interest tied up in the panels

– Makes no allowance for inflationary increases in payments

– Ignores any benefits received after the end of the payback period

A more satisfactory method which allows for these factors is to estimate the internal rate of return (IRR) or yield rate (r) over the whole period of 20 years in real terms. This can be illustrated by taking the Ikea example of a cost of £5,700 and an initial benefit of £600 per annum, or just over £150 per quarter, as payments are typically received quarterly. If inflation was zero over the whole period, these figures would also represent the real returns and even if inflation was, say, 3% per annum, the figures would be increased by 3% but then reduced by the same amount to get a real figure.

An iterative computer programme uses the following equation:

£5700 = 150/(1+r) + 150/(1+r)2 + ···· + 150/(1+r)80

Where r is the quarterly yield rate calculated over 20 years. This works out to be:

0.0215 or 2.15%

The annual yield rate is 100 x ((1+0.0215)4 -1) = 8.89%

To find the gross equivalent monetary rate of return which is the equivalent before tax yield required from an alternative investment, this can be calculated using the following formula:

– Gross Yield = (net real return + inflation rate)/(1 – marginal tax rate)

With an inflation rate of 3% and a tax rate of 20%, a net real return of 8.89% is equivalent to a gross monetary return of 14.86%, while using Ikea’s original savings figures, the gross return rises to 19.86%.

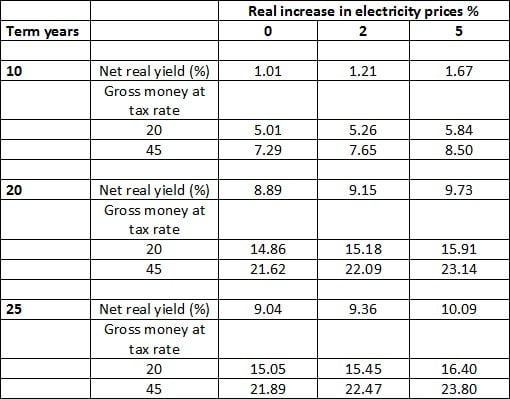

For many people a time horizon of 20 years may be too long to consider, so the yield rate which would obtain after 10 years was calculated which comes to just over 1% with a gross equivalent yield of just over 5% per annum. By contrast, it is possible to add in to the calculation the electricity savings in years 20 to 25, which increases the yield rate to 9.04%. All of these figures are shown in the third column of the table below.

Yield rates from Ikea solar panels

Thus far, the analysis has made no allowance for the possibility that future electricity prices might increase at a faster rate than the RPI, i.e. increase in real terms. In the period 2000-2011, electricity prices increased by an average of just over 3% per annum in real terms and given recent trends this seems likely to continue into the future, perhaps at an even faster rate. Recent pronouncements by the industry seem to suggest that energy prices are likely to rise at a faster rate of inflation for at least 17 years. The figures in columns four and five of the table also show the yield rates obtainable when the cost of electricity is assumed to increase in real terms by 3% or 5% per annum.

Thus, for example with inflation at 3% and electricity prices increasing at 8% per annum in money terms, i.e. 5% in real terms, a 45% taxpayer would need a gross return from, say, a bank account of 23.8% per annum to be as well off as he or she would be by investing in solar panels. Alternatively, a basic rate taxpayer could still make a profit if he or she had to borrow at a rate of less than 15% to install the panels.

Finally, because solar panels reduce the amount of carbon emissions, the homeowner might derive satisfaction from this social benefit, also.

As for the future, some commentators are forecasting that with the continued rise in energy costs and reductions in panel costs, solar energy may not require any form of subsidy from feed-in tariffs, particularly in sunnier parts of the country, to be a significant competitor to conventional forms of investment. This is especially true of the current time when it is difficult to get even a positive real yield from such investments as cash ISAs.

Ken Richards is a freelance finance writer, and formerly senior lecturer in taxation and finance at Aberystwyth University.

Further reading:

Bright future predicted for solar as government learns its lesson

A view from the field: renewable energy in expert hands

Features11 months ago

Features11 months agoEco-Friendly Cryptocurrencies: Sustainable Investment Choices

Energy11 months ago

Energy11 months agoThe Growing Role of Solar Panels in Ireland’s Energy Future

Energy10 months ago

Energy10 months agoGrowth of Solar Power in Dublin: A Sustainable Revolution

Energy10 months ago

Energy10 months agoRenewable Energy Adoption Can Combat Climate Change