Economy

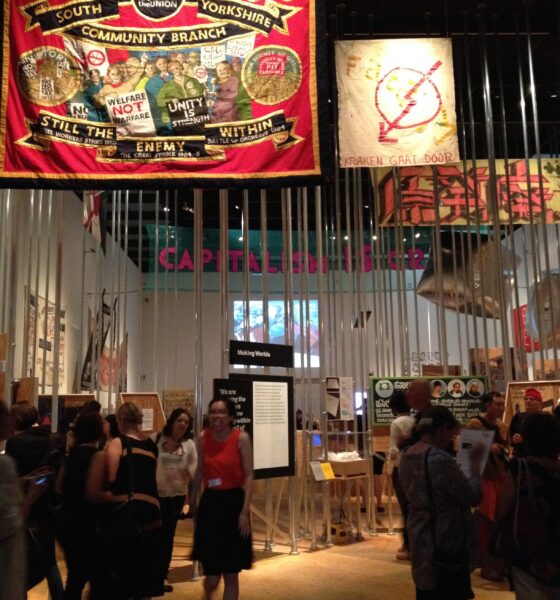

Disobedient Objects: protest art occupies the V&A museum

In a room in London’s stately Victoria and Albert Museum, two inflatable cobblestones now hang in the air like low-budget zeppelins above a troop of cartoonish gorillas clad in leather.

In the entrance to the new Disobedient Objects exhibition – positioned directly opposite some of the world’s finest Renaissance sculptures – sits a battered pan lid.

The subversives and revolutionaries – with their “art from below” – have taken over.

The exhibition is an investigation into the role of objects in movements for social change. The weird and wonderful artefacts chart the recent history of activism and showcase the power that everyday objects have when repurposed for protest.

The inflatable cobblestones, for example, were used in protests in Berlin and Barcelona in 2012. Thrown towards the lines of riot police, the devices make the authorities unwilling participants in an absurd sketch.

The police must throw them back, attack them, or attempt to bundle the unwieldy ballons into the back of their van. Either way, the result looks ridiculous, and inevitably goes viral on the internet.

An inflatable cobblestone hangs above feminine figures clad in leather and gorilla masks - a protest against the treatment of women in art

But that battered pan lid is perhaps the best example of what Disobedient Objects are all about. In 2001, Argentines took to the streets when their government freezing the bank accounts of 18 million people.

Many banged pots and pans, engaging in cacerolazo, a form of popular protest often used in Spanish-speaking nations.

Beaten out of shape, the pan lid still outlasted four presidents. “All of them must go”, the protestors chanted, and four leaders went in just three weeks.

The pan lid’s owner, Maria Teresa Nannini, stands proudly beside it.

“We protested against the banks, but we protested against the state too. The state should have protected us,” she tells me, speaking through an interpreter.

“We waited a long time, because justice is slow.”

After seven years, the bank finally returned her money. Many never saw their savings again. However, Nannini was among the Argentines who felt empowered by their new experiences of activism. She formed a civic action group, which she still coordinates.

“The important thing is something good came out of it,” she says.

Thousands of pots and pans were banged on the streets of Argentina in 2001, in what is billed as the first national protest against neoliberal capitalism

The 99 objects on display – ranging from a homemade gas mask to a robot graffiti artist – were fashioned to protest against an array of injustices, but dissatisfaction with governments and neoliberalism is a common thread.

In the 1980s when representatives of the Indian government, and bank officers, began entering farmers’ houses without warning, beating women, collecting loans and seizing property illegally when the men were at work, a grassroots movement rose against them.

When the union gathered its strength, they began erecting signs warning off corrupt intruders, telling them precisely when they can visit on the farmer’s own terms. One sign now hangs by the entrance to the exhibit.

“It seems like a small thing, but in the Indian system it has been a struggle to preserve the way of life and dignity of the farmers, so this was a huge step,” says Tilly Gifford, who has worked closely with the movement.

“They have achieved amazing things. But after 30 years of the same struggle, you’ll ask them now what their greatest achievement is, and they’ll say ‘Now, when we go to see a bureaucrat, instead of being told to sit on the floor, we can pull up a chair and sit down.’”

Poignantly, not all of the disobedient objects were so successful. A miniature of the Goddess of Democracy statue that Chinese protestors erected at Tiananmen Square, before their uprising was brutally swept away, stands as a reminder of the lives lost in the pursuit of rights and liberties.

But perhaps even more poignantly, many of the objects were fashioned for battles that remain unresolved.

As one of the defining issues of our age, it is inevitable that climate change is well represented.

A Bike Bloc – a four-wheeled, sound system-carrying contraption made of discarded pushbikes – supplies the mood music in the corner of the room. Many like it starred at the protests that surrounded the 2009 UN climate summit in Copenhagen.

Visitors can also enjoy a hands-on experience with a lock-on device. Described as the most successful object in the exhibit, lock-ons are used by protestors to chain themselves together. They can only be forcibly removed using smart saws that can distinguish between flesh and metal.

“There was a particularly scary moment where I thought I’d lost the key,” says one activist.

Many 'Bike Blocs' like this were used to form blockades or decoys at the 2009 Copenhagen protests

Some objects are more complex, such as the game app Phone Story, a subversive protest for workers’ rights in the developing world.

In the game – admittedly not an object – the player must take charge of the supply chain that produced the device they are playing on. Tasks include forcing children to mine at gunpoint, and preventing worker suicides in factories. The app was removed from iTunes in a matter of days.

In many different ways, the V&A’s exhibit reveals the imagination, resourcefulness and determination of social movements.

What unites the objects – from Occupy banners to a slingshot made from a shoe – is the ability of their creators to make something powerful, moving or brilliantly effective from whatever they have.

It is true that many movements cannot be considered wholly successful. Politicians still dither over climate change and workers are still abused in faraway factories.

But as a reminder of what is possible, a teacup sits beside Maria Teresa Nannini’s pan lid. It bears the logo of the WSPU, the suffragette movement that fought for the vote for women in Edwardian Britain. Their cause must have seemed hopeless once too.

And the activists will not stop. Many more disobedient objects will be crafted to fight these causes. Recognising that, the exhibit ends with a blank space, saved for future disobedient objects.

“Activism is never a waste of time,” says one televised activist on the wall above.

“Even if it fails.”

Disobedient Objects opens at the V&A on July 26, running until February 1 2015. The exhibit is free to enter.

Further reading:

Civil society organisations call for action at climate talks

Fossil fuel divestment campaigns can help ‘stigmatise’ industry