Features

Modern Magna Carta: Charter 88

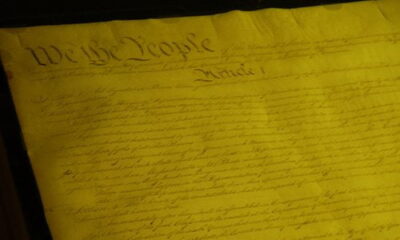

In the lead up to the 800th Magna Carta Anniversary this year Ashley Summers takes a look at the original and a series of modern ‘versions’ of the Magna Carta from the US Constitution to the UN Declaration of Human Rights and various conventions on climate change and sustainability, Magna Carta for the Earth.

It was the lack of a written constitution that drove a group of British intellectuals and activists – predominately Liberal and Social Democrats — to band together and write “a general expression of dissent” letter after the 1987 General Election. The charter, with its name based off of the Czechoslovak Charter 77, calls for constitutional and electoral reform. In addition, to the 348 intellectuals and activists that signed the letter, over 5,000 other people expressed their concerns and displeasure with the state of things in Britain in the late 1980’s and through donations and action, Charter 88 came into existence.

With a soft echo of the Magna Carta, Charter 88 aimed to outline the rights and liberties to be upheld by the ruling government. “We have been brought up in Britain to believe that we are free: that our parliament is the mother of democracy; that our liberty is the envy of the world; that our system of justice is always fair; that the guardians of our safety, the police and security services, are subject to democratic, legal control; that our civil service is impartial; that our cities and communities maintain a proud identity that our press is brave and honest.”

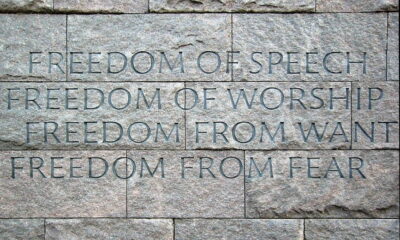

This introduction to the Original Charter 88 resonates across geopolitical boundaries as an ideal that provides for citizens and balances society. While modernity and technology are consistently changing the foundational and constitutional securities should reign constant. Charter 88 called for a “new constitutional settlement” that would:

1. Enshrine, by means of a Bill of Rights, such civil liberties as the right to peaceful assembly, to freedom of association, to freedom from discrimination, to freedom from detention without trial, to trial by jury, to privacy and to freedom of expression.

2. Subject executive powers and prerogatives, by whomsoever exercised, to the rule of law.

3. Establish freedom of information and open government.

4. Create a fair electoral system of proportional representation.

5. Reform the upper house to establish a democratic, non-hereditary second chamber.

6. Place the executive under the power of a democratically renewed parliament and all agencies of the state under the rule of law.

7. Ensure the independence of a reformed judiciary.

8. Provide legal remedies for all abuses of power by the state and the officials of central and local government.

9. Guarantee an equitable distribution of power between local, regional and national government.

10. Draw up a written constitution, anchored in the idea of universal citizenship, that incorporates these reforms.

The charter also acknowledged a truth that has been too prevalent worldwide and is perhaps one of the most honest admissions about the notion of freedom.

We have had less freedom than we believed. That which we have enjoyed has been too dependent on the benevolence of our rulers. Our freedoms have remained their possession, rationed out to us as subjects rather than being our own inalienable possession as citizens. To make real the freedoms we once took for granted means for the first time to take them for ourselves.

Photo: shining.darkness via Flickr

Further reading:

Modern Magna Carta: the original and still the best

Modern Magna Carta: Declaration of Human Rights

Modern Magna Carta: The European Convention on Human Rights

Prince Charles: climate agreement should be ‘new Magna Carta for the Earth’

Cameron, Clegg and Miliband sign joint climate change agreement

Environment12 months ago

Environment12 months agoAre Polymer Banknotes: an Eco-Friendly Trend or a Groundswell?

Features10 months ago

Features10 months agoEco-Friendly Cryptocurrencies: Sustainable Investment Choices

Features12 months ago

Features12 months agoEco-Friendly Crypto Traders Must Find the Right Exchange

Energy11 months ago

Energy11 months agoThe Growing Role of Solar Panels in Ireland’s Energy Future