Features

Time to offload the high-risk, low-return carbon assets

Shareholders are increasingly feeling disgruntled, and rightly, by the risks fossil fuel companies are taking with their money. Gyorgy Dallos of Greenpeace International writes how investors of oil and coal assets face a swiftly deteriorating deal.

In a landscape of increasing operative and regulatory risks and low interest rates, it is time for shareholders to start demanding more. Low bond yields, poor share price performance and lousy dividend payments do not justify the risks.

Bondholders of oil majors, for example, may get only 0.5% higher yields than holders of similar maturity US treasury bonds. Oil companies also retain a vast amount of profit, maintaining a 20-30% dividend payout ratio, compared with other companies such as pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline’s 82% or UK retailer Sainsbury’s 51%. Coal dividend yields are often even lower than those of the oil giants.

In the past 12 months up until the end of February, Shell shares fell 5%, Total by 9% and BP by 11%, underperforming rising market indices. The S&P 500, for example, rose by 10%.

In the US, Arch Coal shares fell by 62%, Alpha Natural Resources 56% and Peabody by 37%. In Europe coal-heavy utilities like Italy’s Enel or Poland’s PGE suffered substantial share price losses.

And the risks are increasing as the economics of coal deteriorates in the US, India and China.

Shale gas is booming in the US and pushing out coal, while renewable energy is pushing both coal and gas out of the European market, depressing market prices. In China, air pollution has sparked public concern and government action.

Deutsche Bank has estimated that global shipments of thermal coal could be 18% lower than forecasted by 2015 should China, the biggest importer, further toughen measures to curb air pollution.

In the US, the Mercury Air Toxics Standard aimed at reducing emissions of mercury and other pollutants will lead to the shutdown of numerous coal power plants. In Europe, the Industrial Emissions Directive is expected to have similar impacts.

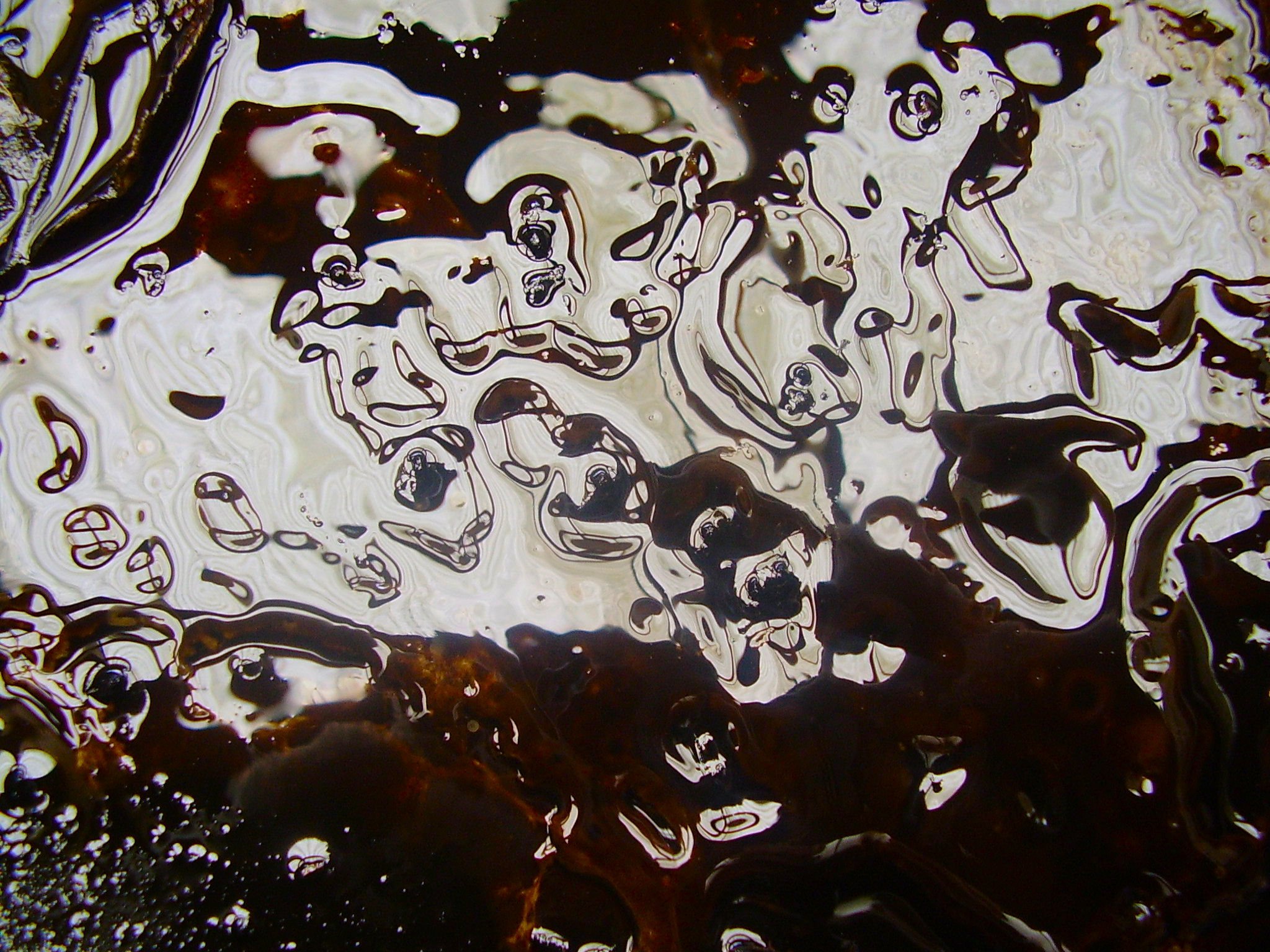

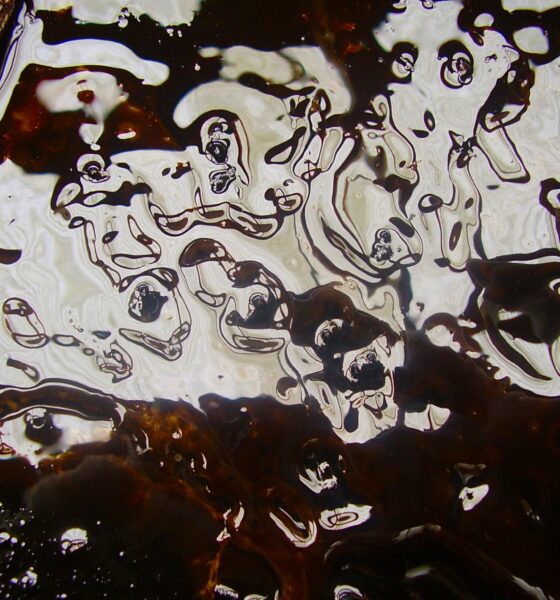

Many oil companies are also pushing into the deepest waters, the tar sands and other highly sensitive environments. Shell has so far invested almost $5 billion to tap offshore Arctic oil in what has only proven to be a fiasco.

These types of projects face huge liabilities if anything goes wrong, such as Chevron’s recent Brazil oil spill. BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil spill have cost shareholders (such as Yorkshire public pension funds) at least $40 billion so far and the total bill might be double.

The near future brings new and bigger risks. Today’s oil and coal assets would likely lose value or be written off if the world adopts stringent emissions reduction targets to limit global warming. HSBC has also calculated that if constraints on carbon emissions were imposed after 2020, they could reduce coal asset valuations by as much as 44%.

Perhaps more significantly, the largest oil and coal companies could become exposed to the issue of carbon liability as disastrous climate events are increasingly being linked by science to carbon emissions. The world’s largest historic greenhouse gas emitters could soon become vulnerable to demands for compensation.

And yet, in a low interest rate environment when pension funds are struggling to balance their books, investors remain overly exposed to these types of assets.

The world’s largest sovereign fund, the Norwegian Government Pension Fund, has Shell, ExxonMobil, BG Group and BP among its top 10 equity holdings, while other pension and insurance funds are often loaded with oil and coal bonds. Anyone buying into the FTSE 100 and other popular indices are exposed to many of the same companies.

And oil companies want to increase that exposure, planning to invest $1.2 trillion in 2013 – half of the UK’s GDP. While a large part of this is expected to be financed from retained profits (limiting dividends to shareholders), a significant share will come through debt and equity issues. Coal companies will also seek hundreds of billions of dollars for projects in Australia’s Galilee Basin or in China.

As shareholders increasingly file sustainability-related resolutions at company AGMs, it’s high time for pension funds and other shareholders to demand higher dividend payouts. More cash back to the shareholders and less investments into the most risky unconventional oil fields seems like a win-win scenario. Increasing oil and coal risks must also be priced into the bonds these companies offer.

Investors must urgently rethink if they really want to maintain such a large, and potentially costly, exposure to these high-risk and low-return oil and coal assets.

Gyorgy Dallos is a senior advisor at Greenpeace International

Further reading:

Claims of oil prosperity fail to note the finite nature of fossil fuels

Campaigners criticise ‘short-sighted’ government energy policy after oil boost

Report urges oil investors to hold companies to account over responsibility