Features

Post-horsemeat burgers, has Tesco returned to business as usual already?

In response to Tesco’s statements about the horsemeat scandal, I offered a spoof apology for the supermarket chain: the apology I wished it would have offered.

Over the following weeks, the ads kept coming. Tesco bought up full page and double page spreads across the print media, which were also read aloud as radio ads. They are stacked up as fine printed flyers in its supermarkets (yes, I still go there) and presented as helpful customer service information. Unsurprisingly, they were hardly flying out the door in my local store.

The campaign certainly attracted attention. The BBC’s Brian Wheeler compared Tesco’s words to Shakespeare and admired their “strangely poetic quality”. Tongue-in-cheek, he sought expert comment.

“It resembles poetry in the way that it is laid out”, said poet Matt Harvey. “It gives the words a portentous quality. They are reaching for gravitas, and probably achieving it.”

But did the ads actually work? Brand Republic’s Claire Beale observed that this is “such a crucial time for the Tesco brand” and imagines the copy writers would have been putting in some long shifts. For her, Tesco implied some respect for its audience, showing “perhaps (finally) some empathy and certainly some humility”.

However, Tescopoly author Andrew Simms said (in the Brian Wheeler piece), “Until Tesco can prove it really has changed its business model, and is making fewer demands on suppliers, the campaign is just ‘mood music’”.

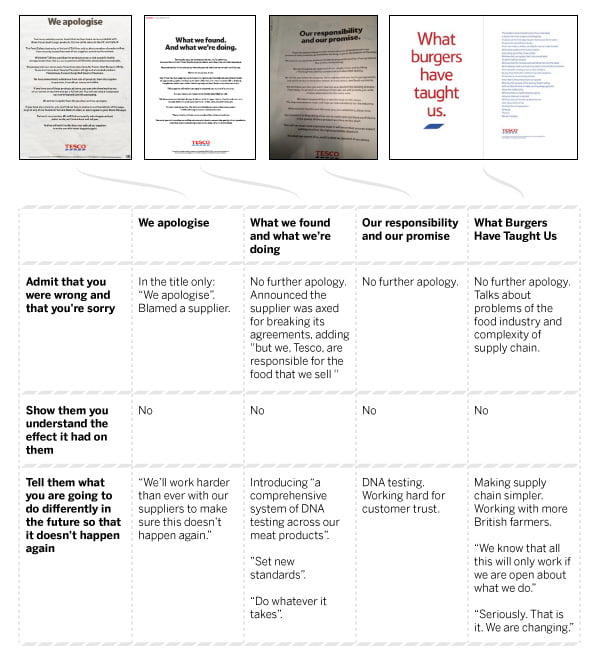

What intrigues me is the extent to which anything has changed for the company or for its stakeholders. Assessing the ads was illuminating. Mark Houston, writing in the Harvard Business Review, provides us the means to make a semi-scientific appraisal by suggesting three key ingredients which are integral to an honest and meaningful apology:

1. Admit that you were wrong and that you are sorry

2. Show you understand the effect your wrong doing has had on those you apologise to

3. Tell them what you are going to do differently in the future so that it doesn’t happen again

Against these criteria, this is how the Tesco ads stack up:

I know how I feel about these ads. I am not moved. To be honest, I am really irritated by them. Looking at the three criteria: the apology took forever to arrive and was fleeting once it had; the admissions of wrong doing and causing hurt were non-existent; and the ‘what we are going to do differently’ seems inseparable from what they are doing now.

I know how I feel about these ads. I am not moved. To be honest, I am really irritated by them. Looking at the three criteria: the apology took forever to arrive and was fleeting once it had; the admissions of wrong doing and causing hurt were non-existent; and the ‘what we are going to do differently’ seems inseparable from what they are doing now.

For me, and I suspect for the great majority, this feels like another big business going through the motions.

When you are the biggest and most powerful player, it is ridiculous to blame the industry you are part of and which you shape more than anyone else. Of course supply chains are complex and murky. Apologise for your part in making them so. Do not play the victim.

My view is that many people are deeply disturbed by the worry that horsemeat from criminal gangs has entered the food chain. What else might be in the food that we have been buying from manufacturers and supermarkets, which have all been banging on about their quality and trustworthiness for decades?

It may turn out that the ‘bute’ levels are insignificantly low; that human health was not put at risk. Let’s hope so. But what also of the devastation, for example, of those who do not eat pork because of their religious convictions when they discovered they likely have been eating meat from the wrong animal?

The total lack of empathy for the huge numbers of people that learned that they were unwittingly feeding God knows what to their families is striking.

And what really will change from now on? Given contaminated beef supplies came from the UK and Ireland, forgive me for not being impressed by the announcements on the provenance of chicken from July onwards.

In respect of introducing new testing that is “world class“, shouldn’t this already be the case for companies selling food to millions of people every day? What else would be expected of the UK’s largest retailer? Does this new iteration of “world class” have any meaning for anyone?

Andrew Simms persuasively suggests the business model is the problem. Of the two local stores within two minutes walk from our office, one still offers in-store ‘apology’ related information; the other does not. What is much more difficult to miss are the new print ads in the London free print media. Ads which highlight the low cost of food at Tesco, and at the same time, a business model and modus operandi which remain entirely unchanged.

Business as usual is not part of the problem, it is all of the problem. Words alone – especially these words – are inadequate. We’ve heard it all before.

This is the reality Tesco must face up to. If it is serious about change, it should prove it. Until then, this is simply more of the same.

Michael Solomon is director of Responsible 100.

Further reading:

The apology big food brands should be offering

Government scapegoating retail for horsemeat scandal is pathetic

Defra: horsemeat in lasagne ‘cannot be tolerated’

Taking steps towards a new ethical age of business

Merging the great business dilemma: profit v sustainability, responsibility and ethics

Environment12 months ago

Environment12 months agoAre Polymer Banknotes: an Eco-Friendly Trend or a Groundswell?

Features11 months ago

Features11 months agoEco-Friendly Cryptocurrencies: Sustainable Investment Choices

Features12 months ago

Features12 months agoEco-Friendly Crypto Traders Must Find the Right Exchange

Energy11 months ago

Energy11 months agoThe Growing Role of Solar Panels in Ireland’s Energy Future